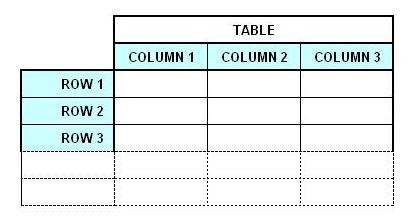

Data are stored in tables. Each table consists of

horizontal rows, and each row is an identical sequence of fields. The repetition of

these, row by row, forms vertical columns of fields. Thus, the structure of

data is represented as a table of rows and columns.

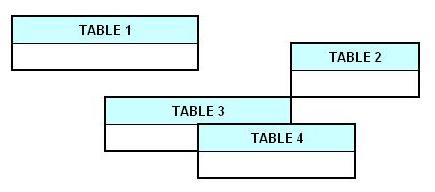

A collection of tables is called a Database.

To demonstrate, we will create a simple database, called

_YourData. There will be one user, ‘user1’, whose password is ‘password’:

These are three different SQL commands.

Each command is terminated with a semi-colon, or ';' character,

which tells the DBMS to execute the command.

The first command tells the DBMS to create the _YourData database,

and compose it of latin1 characters. (Don't worry about the "latin1" term;

it's not really the latin you learned in school.)

The second command tells the DBMS that every subsequent command will be applicable only to the _YourData database, and not to any other.

The third command creates the username and password.

Let’s begin with a simple data table that you are

familiar with: your phonebook. In its simplest form, it consists of three

elements: names, addresses and phone numbers. Therefore, your data table,

called _Phonebook, will consist of three columns.

Each column may be referred to as a field.

Because SQL reserves

certain words for itself, we will prefix all our field names with an

underscore, or '_' character, to avoid “name collisions”. Thus, our column names are

_Name, _Address, and _Number.

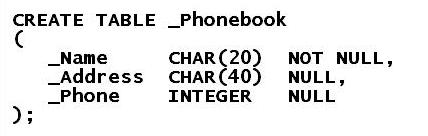

You will create this _Phonebook table with the command:

Let’s break this down. CREATE TABLE (…..); tells the

DBMS to create a table. Inside the parentheses, you “define” your three fields.

Each field, or column, is separated by a comma. For each field, you define its

name, data type, and whether or not it can be empty, or NULL.

Data types are simply a way of telling the DBMS

what you kind of data you plan to put there. For instance, CHAR(20) means that your _Name

field will consist of 20 or less characters, such as

‘A’ or ‘z’. INTEGER is just what it says, an integer, referring to a numerical

value that can be added, subtracted, or whatever.

Other data types include

FLOAT, DECIMAL, DATE and TIME. With small variations, these

are consistent across DBMSs. I’ll cover these more in the Data

Types section.

NULL versus NOT NULL identifies whether the field

is allowed to be empty or not. By using NULL, you are saying that the

_Address and _Phone fields may be empty; that is

useful because you may want to leave them blank and fill them in later.

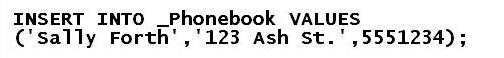

Once you have created an empty _Phonebook

table, you will input data like this:

Congratulations. You have created your very first

record, or row of data.

Note how the above command resembles simple English. Just like a spoken command, you have told the DBMS to INSERT

your data into the _Phonebook table.

Unlike a spoken command, however, you must

adhere strictly to the rules of SQL. One misplaced comma, one forgotten quote

sign, and you will be mercilessly harangued by the DBMS for the grievous crime of

committing a “syntax” error. In those cases, however, it is just a matter or

going back and fixing the problem before retrying.

You may insert as many records as the DBMS allows you.

Some DBMSs allow for billions of records, while some cap it at a few thousand.

A note about formatting: The DBMS parses SQL by

treating indentations and new lines as spaces. Therefore, you may use

indentations and new lines as you wish. I use them interchangeably

throughout this manual to make my

operations easier to understand.

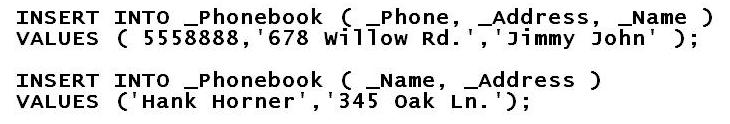

Here are a few more INSERTS. Note how we can

reorder the fields, or even leave them blank.

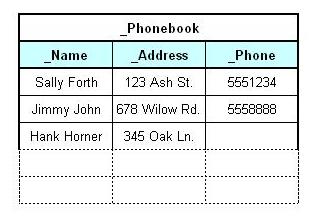

After these, your _Phonebook table will look like

this:

So, in the course of a few SQL commands, you have

created your database, user, table, and the first records.

Data are not very helpful unless you can read them.

The SQL token for reading is SELECT. A SELECT command is referred to as a "query".

SELECT can be used in a variety of ways. You can

retrieve everything from your table. You can retrieve just one column. You can

retrieve just one row. You can retrieve just one column from just one row. If

you are not sure what you are looking for, you can go fishing.

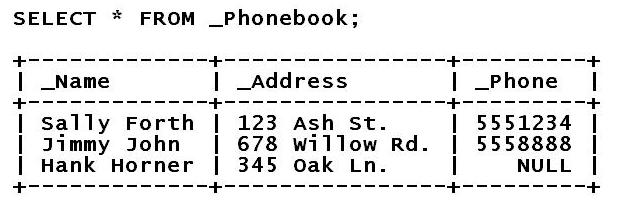

The asterisk, or '*' character, is a SQL token for “everything”.

Therefore, if you want to retrieve the entire _Phonebook table, you will enter

the command:

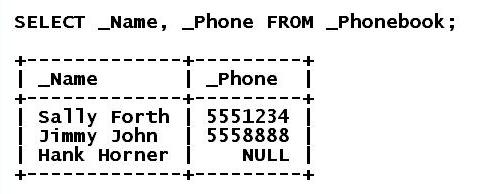

If you wish, you can also specify individual

columns. For example, if you want to pull the _Name and _Phone column, you will

enter:

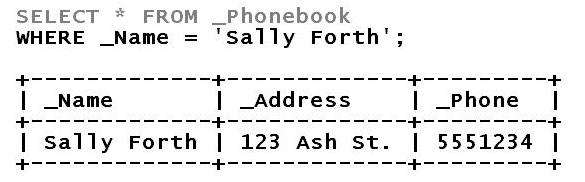

If you want to specify which record or records you

want to retrieve, you may do this with the ‘WHERE’ token. This limits the

output to only those records which match your requirement.

This requirement is called a

“conditional”. The WHERE conditional is often referred to as the "WHERE clause". In its simplest form, the WHERE clause would be a single field containing a

single value.

By now, you can see that SQL is a very simple

language. The trade-off is that you must be absolutely precise in your usage.

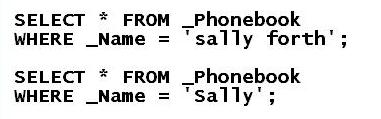

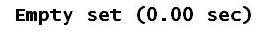

If you enter either of the following, you will get nothing.

These will both return an empty set:

The first empty result is

because you used lowercase letters. Since the data are "case-sensitive", this

is like misspelling Sally’s name. The second is because you entered an incomplete

search string. Since the query looks only for Sally’s first name, it does not match

your original string of characters.

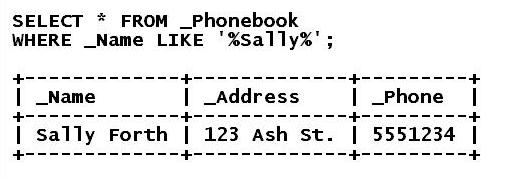

If you're unsure, you will need to use the ‘LIKE’ token. This tells

the DBMS to query the table with a fuzzy comparison. For instance,

you know that ‘Sally’ is part of her name. You would use the ‘%’ character

as a wildcard, entering:

So,

any kind of immediate data retrieval will start with 'SELECT'.

By now, you can see that the SELECT query will be your new best friend.